[ad_1]

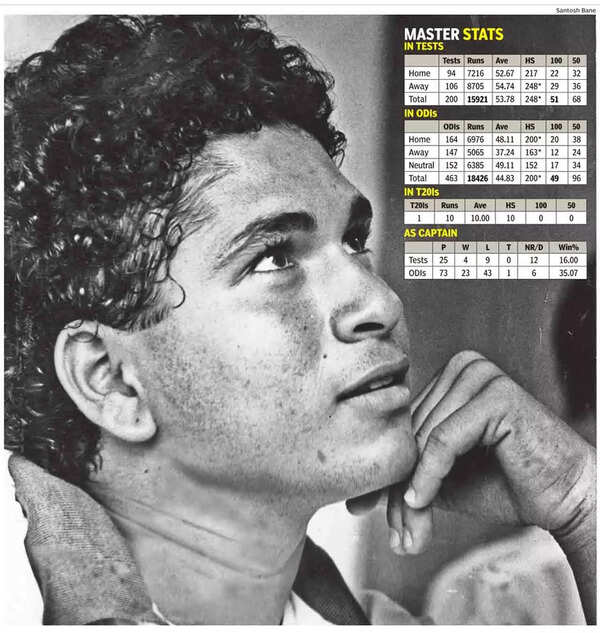

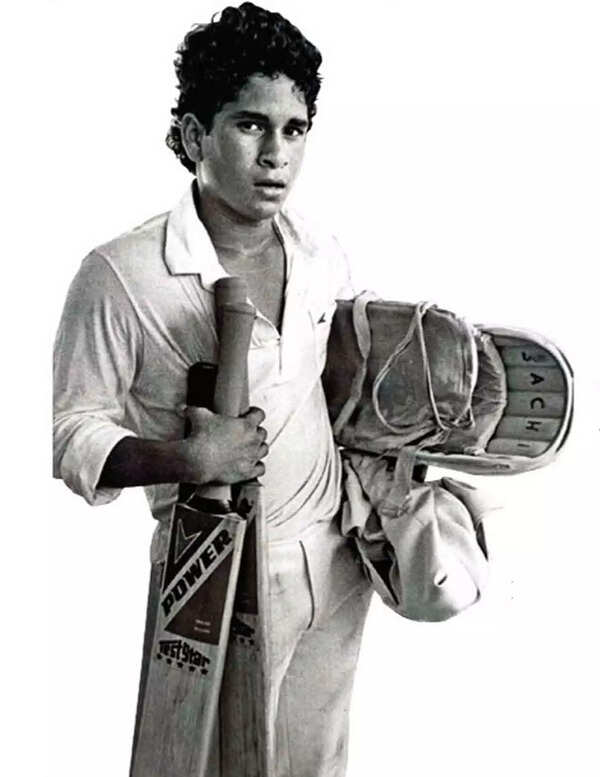

Sachin Tendulkar has turned 50. Read that again. SACHIN TENDULKAR HAS TURNED 50. How could he? We still remember him as the curly-haired, baby-faced boy wonder of 16, who battled the fiercest of fast bowlers aged 16 in 1989, in Pakistan, with a bloodied nose, refusing to take the sagely advice of the more battle-hardened colleagues to retire hurt with a stern shriek. “Nahin, main khelega”.

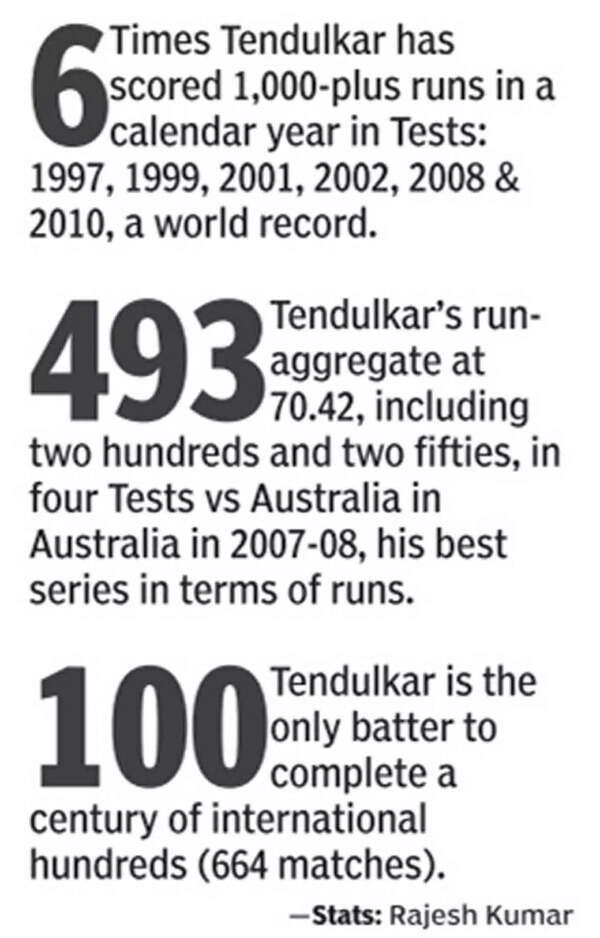

But Tendulkar is nothing if not a man of milestones. He just had to get to another 50, even though he retired ten years ago. And this one feels different to the 68 half-centuries he has scored in Tests, the 96 he cracked in Odis, the 116 he smashed in First-Class cricket and the 114 in List A games.

Add to those the 16 he got in T20s, mostly in the IPL.

“This is the only 50, where I don’t feel 50,” Tendulkar, looking fresh and young in deep blue floral printed shirt and denims, sporting just a few traces of salt and pepper in his day-old stubble, tells TOI during a 52-minute chat at his sprawling Bandra Bungalow, which almost kisses the sand by the seaside at Perry Cross Road.

You know you are breathing rarefied air when you look at the rich collection of trophies in Tendulkar’s cosy study, as you wait your turn to interview him. A picture of the only cricketer to score 100 international centuries accepting the coveted Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, peeps at you. Your eyes soak in all the accolades that he has won and a collection of newspaper headlines that scream “God” and then they meet the legendary frame of him walking out to bat at the Wankhede for one last time on November 14, 2013 against West Indies, and the crowds in the stands clicking the moment on their phones.

As you are led to Tendulkar’s spacious living room and you park yourself on the elegant sofa next to him, you ask him what turning 50 feels like. “I jokingly say, I’m still a 25-year-old with 25 years of experience,” he says with a chuckle. An evening spent with close friends and family members, fooling around is still his idea of fun.

Not as much fun though as talking about his greatest love. Batting. And batting long hours. And this is the only area where he lets humility briefly marry narcissism.

While he has reviewed many knocks in his mind, YouTube has now allowed him to watch them again. Like many sports fans who befriend the internet and swat away depression by watching a Tendulkar extra-cover drive or a Roger Federer one-handed backhand.

“I watch my knocks, sometimes,” he says, and adds, “In fact, I watched one last night. The 179 against West Indies at Nagpur in 1994. I wanted to see one shot,” he says with his eyes lighting up. The enthusiastic shift towards you, indicates it is a shot that pleased him.

You want to know more.

“It was a back foot punch, more of a firm defence which I had played to Courtney Walsh. It bounced on the surface (claps his hands) as the wicket was hard and went over Walsh’s head for a boundary. I wanted to watch that.”

You remind him that on 99, he violently pulled Walsh for a six to get to his hundred. “I wanted to watch that too,” he says, with his face awash by a cocktail of self-effacement and childish joy.

In between those sixes and fours though, there were thousands of deliveries that tickled the ribcage, crushed the fingers and made him put his head down and meet the ball underneath his eyes. The determination to bat long was ingrained since he was 12. Ask him if it is a facet that has gone missing in today’s cricket and he takes a generous pause.

“The game has also changed after newer formats have been introduced,” he analyses.

“T20 has taught batters a new dimension. You need not defend. You can have an impact by playing 75 balls or lesser. The rules have changed too. But I still feel that if someone is bowling well, one should have the technique to survive for some time. You can’t say, main to maroonga and say, even if I get out, I always have another match. Play the situation. It is like if I am having Japanese food, I will use chopsticks. If I am eating ghar ka khaana, I will use my fingers. While eating continental fare, I’ll use fork and spoon,” he stresses.

But concentration and technique are different, you argue. A rigorous preparer, who romanced toil and the odour of sweat, Tendulkar counters, “You improve concentration by challenging yourself in practice. It helps to bat long hours, and just when you feel you are about to lose focus, you pull up your socks and tell yourself, last ten minutes, last ten minutes.”

Ask him the secrets of improving focus, and he says those four golden words. “SWITCH ON, SWITCH OFF”

“When I was at the non-striker’s end, I would look to switch off. At the striker’s end, I would wait till the bowler started his run up and be at 90%. It would be at 100 % when he was at release point.”

Tendulkar says batting is all about picking up signals from the bowler. “If you are sharp, you will pick those up. Even before the ball is released, you know what is coming at you. Inswinger, outswinger, bouncer, split-finger slower one, the way a bowler hides the shine to cover the grip, I would watch that. It gave me extra time,” he says.

If you were privileged enough to cover Indian cricket through the 90s and 2000s and watch net sessions, you would have noticed Tendulkar carrying on in the nets even after the coach or support staff yelled, “Last round”. You remind him about that, and he says, he had that trait even in school.

“I just enjoyed batting,” he says, his eyes radiating that love for his craft. “Even if I was batting well, I always was just happy, never satisfied. I never wanted to get out of the nets. Achrekar sir, had to pull me out.”

So, what was a satisfactory net session for him?

“The sound,” he emphasizes, with a voluble tock. “To me, my batting was all about that sound I heard. When I played the ball, that sound told me whether I was batting well or not. I may or may not have scored runs. But that sound told me what I was doing. Whether I was moving well, or not. A batter needs to hear that. When you hear that perfect sound, it puts you in a different zone. If I did not hear it, I would focus on quantity and volume, till I heard that sound,” he stresses.

Was 1998, the year where the captaincy was taken away from him and he recorded probably his greatest season and had arresting duels with the late Shane Warne in India and Sharjah, the year when the sound was the sweetest, or was the sound sweeter when he had that amazing second wind, post the 2007 World Cup, where he rattled off 24 centuries in a prolific four-year period?

You try to suggest that maybe he did something different in 1998 than 1997?

It is the only time in the conversation that you sense a semblance of agitation on his face and tone.

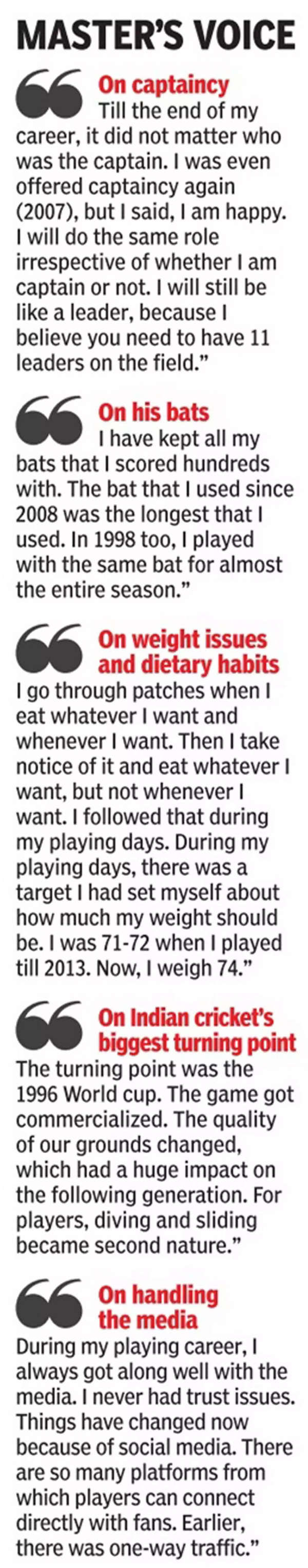

“I did nothing different to what I did in 1997 when I was captain. There were a number of things that were falsely reported that I was struggling. Yet, I scored 1000 runs in both formats and if I am not mistaken, that year, I was the only cricketer to do it. Those days, I felt, reporting was not done properly. To me, whether I was the captain, or just a player, winning mattered more than anything else.”

What was more enjoyable for him, then, the purple patch of 1998, or the golden sunset of 2007 to 2011? Tendulkar says, for him, it was enjoyment factor that counted the most. And in that second wind, he says, he was enjoying his cricket.

“Enjoyment keeps you in the right space. Mentally, if you are in the right space, you think better. There is fluidity in whatever you do. Your movements at the crease are unrestricted. For me, batting is all about how you react. Every ball, a bowler is asking us a question. And to answer that question, if your mind is complicated, and you lose 0.45 seconds, it is already too late. That is why on certain days, a bowler who is bowling 135 can rush you, but on another day, even if someone bowls 150-plus, you feel you have time.”

This business of great players having extra time, makes for a fascinating chat and you ask him, whether that is really true and how that is possible.

“You have that extra time when you are playing one ball at a time. When you get rushed, you are playing multiple balls at one time. One is the actual ball and the other is the imaginary one that has never been bowled. If there are multiple things going on in your head, you end up playing at the imaginary delivery. And by the time you realise that you are late and are caught on the move.”

The conversation smoothly veers from skills and preparation into the art of preserving one’s body for the brutality of elite competition. Over a decorated career of almost 24 years, Tendulkar’s body was ravaged by injuries, both old and new and the one that hurts him and his countless fans most for its almost tragic heroism, is the back injury he suffered during his epic 136 in the fourth innings at Chennai vs Pakistan.

As he uncomfortably shifts in his seat, Tendulkar’s voice turns sombre, and his eyes reflect the reservoir of pain. “I still remember, it started happening before teatime. At teatime, I was in the dressing room lying on the floor, with my feet on a chair as I was trying to relax my back. I told my teammates that I am going to try and accelerate. Because the way my back is acting up, I don’t think I have enough time.”

You log in to your own memory bank trying to recall that cruelly tense January Sunday afternoon and ask him did the pain cause him to hit Saqlain Mushtaq for four boundaries in an over.

“Yes,” he says and analyses his dismissal with India 17 away from a famous win. “But that is when the bounce did me. The ball (off Saqlain) bounced a little more than what I had expected. We were six down, and we still had four wickets in hand. I thought I could finish the game a little earlier by taking more initiative.”

Tendulkar reveals he travelled to Australia and England to get his back sorted out. “I was also told that I may have to get operated. I did not eventually. But the injury troubled me for a good six to eight months.”

In August 2004, he also made all his fans google Tennis Elbow after he was diagnosed of the condition in Holland where India were playing a Tri-series. “It troubled me for a year. I tried taking injections and went through several treatment methods, but things settled down only after my surgery.”

(PTI Photo)

The Master reveals that from 2007 to 2011, when he scored those 24 centuries, he was suffering from Tennis Elbow and a Golfer’s Elbow on the right hand. “If you see my videos from that period, you will see me wearing protection on both sides. After every practice session, I would ice my elbow. But my previous experience had taught me how to manage the injury.”

Tendulkar reckons when you get injured matters a lot in the treatment of the problem. “Very few know that Rahul Dravid also had a Tennis Elbow injury. But his injury happened towards the end of the season in 2002 or 2003. Rahul told me, for the next three months, he won’t lift a bat. And his injury had healed. To me, it happened at the start of the season.

“I had no option but to pick up a bat and play 100-plus balls every practice session. That ensured, I sank slowly, but surely.”

Experts reckon, the pre-Tennis Elbow injury Tendulkar was more thrilling to watch. Post 2004, while he became more prolific, the run-making, according to analysts, seemed more efficient but less exciting. For a batsman naturally blessed with a wide array of shots, how ego-puncturing was it to give up some of the shots to ensure that the injury does not worsen?

“They were in there somewhere. But after the 2003 World Cup, I had my finger operated. That injury actually happened in New Zealand in 2002-03 before the World Cup. It took me about four months to recover. I felt my grip and my style of playing had changed because of that. In the following year, I suffered from a Tennis Elbow. I do not know if everything is related now. From here, (shows his grip) when you change your grip, it impacts your hand. In 2005, it was my right shoulder and bicep that had to be operated. In 2012, I injured my wrist. All these injuries impacted my grip and my back lift. That is the reason I felt certain shots… (leaves it unsaid).”

Tendulkar reasons that the brain understands the body better than anyone else. “The brain shuts down certain parts of the body and forces you to make subtle adjustments. And I felt somewhere without me realizing, those changes (cutting down on certain shots) had happened.”

(PTI Photo)

But he was also the most analysed batter by rivals and opposition teams and cutting down shots may have something to do with captains blocking some of his good shots. Tendulkar replies in the affirmative and adds, “That also caused me to change my playing style. If there is a widish mid-wicket, I am going to try and place the ball to avoid him and play straighter, towards mid-on, which might seem like I am avoiding the shot over mid-wicket. The shots that I may have cut also depends on what my role was in the team.”

Tendulkar’s body did go through the wars a fair bit, but his eye was still intact. That eyesight, which allowed him to get in position early and allowed him to pick up length earlier than mortals, was what made him revered.

The great Sunil Gavaskar took care of his eyes by not reading in moving vehicles, dim light, and by taking care that pens and pencils of emotional fans seeking autographs do not get near his face. How did Tendulkar nurture his greatest gift?

“I did not do anything specific,” he says. “Because I was practising and focusing so hard, whenever I went to ophthalmologists, I was told that my eye muscles are strong. That allowed me to focus. I was also able to directly look into the sun. There were a number of guys who found it difficult to catch the ball that came out from the sun. Even today, if I have to catch a ball that comes straight out of the sun, I might find ways to do it despite looking directly into the sun. Right from childhood, I used to play hundreds of deliveries every day with intense focus. That strengthened my eyesight.”

Tendulkar never shows off at the best of times, but he does indulge in a bit of it by reading the smallest font on his phone without glasses and contact lenses and reveals he still has 20:20 vision. “That way, it’s nice to still be in the 40s. I don’t know how long it will last,” he jokes.

(PTI Photo)

A creature of habit, Tendulkar reveals the one thing he never gave up doing from November 15, 1989, at National stadium, Karachi to November 14, 2013, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai, was packing his bag and ironing his kit the night before a game. That was his trigger.

“When I saw my clothes pressed, I knew that tomorrow there is something important happening. And I would start switching on. Also, on match-day mornings, I would always make my own tea in my room.”

The latter makes you curious and you goad him into revealing why he did that when the entire hotel staff would be more than willing to serve him tea.

“It was part of my preparation. I did not want to see anyone in the morning. If tea was not available in the room, I would always tell the person who served it, to leave it outside. My room on a match day was MY SPACE. It allowed me to think about the game without anyone disturbing me. I HAD to be in that zone.”

You ask him if he felt he was in that zone when he was making his retirement speech, which even today, if people need a good cry, plug in and play. And you ask him how much did he prepare for it?

“I didn’t prepare at all,” he says animatedly. “We were to have a press conference a day after the Test ended. But the Test ended on Day Three. Star TV asked me, we will ask you three questions, is it fine?

I told them, is it ok if I speak, rather than answering just these three questions. The sequence that was planned was like this: I would speak first, then the man of the match, man of the series, Darren Sammy and then my three questions. At the end, Dhoni was to speak, and we were to go and take the trophy.

I told them, is it ok if I change it a bit. They said ‘fine’. But I said, it will be more than three four minutes. They said, ‘go ahead.'”

Tendulkar reveals that he only had a list of people who he wanted to thank and no prepared text. “Whatever I spoke, it just came out. I knew who I was going to talk about and the simplest thing I did was I just arranged everything chronologically. It was very difficult emotionally, though. I kept sipping water to avoid choking and tearing up,” he says.

10 years of living as a retired cricketer has not diminished his love for cricket, but Tendulkar says he does not watch too much of it on TV. However, he has interesting views on the three formats.

“In T20s, can we find a balance between both sides bowling in the second half of the game and batting in the first half? I would love it if ODIs are split into four innings of 25 overs each. But a team has only 10 wickets. You decide how you want to use your batting resources. It brings the support staff into the game too. We also need to think of going back to one ball, because today there is no reverse swing and field restrictions make it impossible for spinners to change their line.”

And what about the format that is considered the purest, Tests?

“We must acknowledge that at the heart of Test cricket is the pitch,” he stresses. “We have two versions that favour batters, Test cricket needs to favour bowlers. You have introduced two versions where every ball or over, there is something happening. You do not want to have Test cricket on dead tracks. We keep hearing Test cricket is our no.1 format and we must revive it. We can revive Test cricket only if bowlers are able to consistently ask batters challenging questions. Let us not talk about how many days the game is going to last,” he adds.

Having had his fair share of injuries and rehabs, you ask Tendulkar about cricket fitness and gym fitness in these days of workload management and preservation. His views are simple, but deep. “Batters, keepers, fast bowlers and spinners, everyone’s requirements are different. After looking at them, you decide how you train, how much you train and when you train. The way one trains in the off-season, you cannot do that in the middle of the season.”

Tendulkar stresses on skill-based training for overall development. “I keep hearing things about not bowling too much in the nets. Yes, you must not over bowl. But it is equally important to not under bowl. Because the skill sets that a bowler develops, he develops only when he bowls. If you keep conserving yourself, instead of 24, you are going to develop those skills at 28. All the leading bowlers I have spoken to have told me that they had to bowl to get better. Same with batting. If I just keep facing limited deliveries every day, I am not going to get that variety,” he states.

As the chat nears its conclusion, you ask him if turning 50 will make more people seek his counsel as one assumes by that age an individual has experienced most of life’s ups and downs. While Tendulkar remains a generous tipper with cricketing views, do young players also come to him for financial advice? After all, he was the first Indian superstar, to be managed by a firm, something which became a norm in later years?

“No, they don’t,” he says, laughing, but turns serious, quickly. “If they do, I will tell them to have a personal advisor, whom they can trust. Involve close family members too. Have knowledgeable people around who have good intentions for you.”

Tendulkar says, his family always took care of everything else off the field which allowed him to devote himself single-mindedly to cricket. “We took nothing for granted. We valued everything that came my way. And it was hard-earned money. We never splurged without thinking properly.”

He concludes with a prophetic, “You will keep getting introduced to newer things in life, but never forget your roots.”

(Reuters Photo)

[ad_2]